The Vido-InterVac Facility (Photo credit: VIDO-InterVac)

The Vido-InterVac Facility (Photo credit: VIDO-InterVac) All these questions and so many more were rolling around in my head as I made my way through the tall oak doors and fought my way upstream through the tumultuous crowd of first-year med students filling the hallways from wall-to-wall. After a few minutes of wandering and checking maps, I found myself standing before Dr. Napper’s office. Despite having had a little trouble finding it, I was glad that he had chosen to meet me in his Health Sciences office, rather than in his office in VIDO-InterVac (the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization-International Vaccine Centre) where he normally works; I had heard from others who met him there that the security for such a meeting is insanely rigorous, involving visitor passes, background screening, and potentially biosafety training, depending on where in the building you have to travel. Which makes sense, I suppose, in a building housing a level 3 research facility and containing some really nasty organisms (tuberculosis, Zika virus, and Coronavirus, to name just a few).

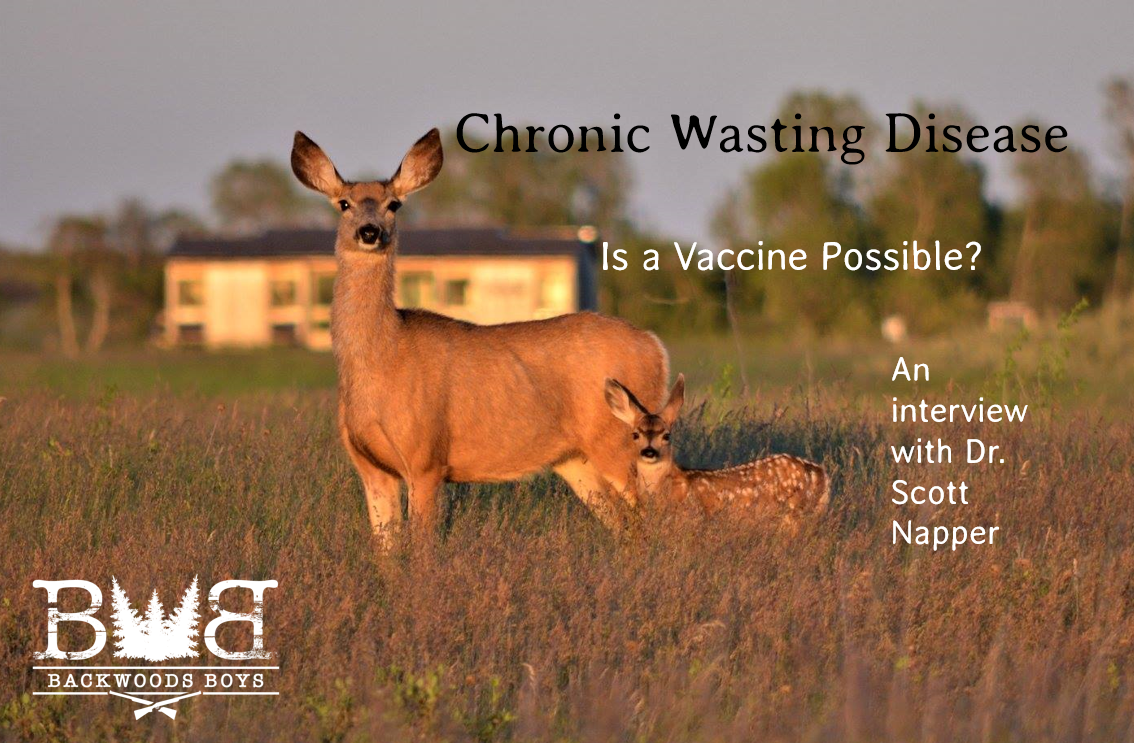

For a guy who works in such an intense environment though, Scott has a surprisingly warm personality. Quick to smile and tell his students that he has his daughters’ names tattooed under his shirt (as chains of amino acids of course, such that spelling out the amino acids with their alphabetical codes reveals the girls’ names), he is one of the most welcoming scientists I have met. His door is open, and before I can knock, he booms out “Dale! Good to see you again, come in and take a seat!”

Dr. Scott Napper, from the U of S (photo credit: abic.ca)

Dr. Scott Napper, from the U of S (photo credit: abic.ca) “It is definitely different,” he agrees, “but it’s the same basic principle. With a virus, you have a clear situation of ‘here’s you, here’s the virus,’ and as long as the antibodies only attack the virus, you’re good. With a prion vaccine though, it’s almost more like a cancer vaccine, because it’s a part of your own body that has turned against you. A prion protein has one particular shape in the healthy form and another shape in the unhealthy form. So what our research has been doing is targeting regions that are only exposed and available for antibody-binding in the unhealthy form. We call those DSE’s or Disease-Specific Epitopes, and we identified three of those. We developed three potential vaccines, each one targeting a different DSE on the CWD prion. Theoretically, what would happen is that if I vaccinate you with it, and you don’t have the prion disease, the antibodies come along, they see your healthy prion protein, and they don’t even recognize it. But if you DO have it, they recognize it and bind to it. So they only attack the misfolded pathological species.”

He then goes on to describe how they tested the first of the 3 potential vaccines. “The first one we made was against a YYR target, this Tyrosine-Tyrosine-Arginine site, and that worked when we tried it in sheep. We vaccinated healthy sheep with it and watched them for four years, and there was no sign of the disease—indicating that the vaccine doesn’t cause spontaneous misfolding of healthy prions. Then we moved on to elk and deer and saw the same thing—no sign of any prion. So it was safe. But when we vaccinated elk and put them on infected land, the vaccinated group actually came down with CWD a bit faster than the unvaccinated control group. Now, it was a small amount—barely statistically significant—but it was significant. The only options for the vaccine were that it 1) worked, 2) did nothing, or 3) made things worse, and in this case, it did seem to make things worse. We don’t know the exact reason, but there are two main possibilities.

Either a) the antibodies are binding the low-level prions that were always passing through the gut and sort of ‘sopping them up’ into the body accelerating the disease, or b) the antibodies are binding the healthy form of the protein, causing it to misfold. But based on the results from the first experiment—where the sheep, elk, and deer did not show any sign of prions after 4 years—I really think it is the first option. They are binding prions from the gut, promoting their uptake, and increasing the number of prions taken into the body. Now this is fixable, and whether one of the other 2 vaccines might work perfectly as-is is a distinct possibility, but unfortunately, we have not had the funding to test more than the first one. But even if the other two vaccines were tested and ran into the same problem, there are work-arounds for that. We know when antibodies bind, which part is responsible for mediating uptake into the body. We can engineer antibodies to not have that, so they would still be secreted in the gut, still bind to the prion, but not be taken up. It gets a lot more complicated [on the production end], but it can be done.”

“Absolutely!” he said. “Actually, when I began working on this vaccine, it was intended simply as a prion vaccine, and the primary focus was going to be BSE. But the cattle industry was worried that any talk of a BSE vaccine being developed would lead to panic as people start thinking that it is out of control (when we would simply have been acting pre-emptively to a large-scale break out) and so we were told not to call it a BSE vaccine. Since it would work just as well for CWD, however, we just decided to shift focus to the CWD aspect, and let it be used for BSE once it is completed. It is, in reality though, a prion vaccine that will work for any prion disease. This CWD vaccine, once completed would work equally for BSE, scrapie, Creutzfeldt-Jakob’s in humans, and any other number of prion disease.”

I was blown away by the implications of such a universal vaccine. The impact it could have on the livestock farming community as a whole is spectacular. However, as I frequently remind people, the farming community is only part of the puzzle. We also have to consider impacts in the wild. A vaccine for CWD would certainly be of use in the wild, but to what extent? I wondered. I briefly highlighted part of my discussion with Dr. Haley regarding CWD resistance and mentioned that such resistance could potentially act as a safety net—in an ‘all-else-fails’ situation, at least some animals should hopefully remain CWD free—and asked Scott how he felt the vaccine would be of use in wild herds. He noted that while he does find it hard to imagine that CWD could wipe out cervids completely from the Earth, species do go extinct all the time, sometimes due to infectious diseases. So while he would expect that natural selection of whatever more-resistant genes exist would lead to some cervids surviving, "we have to consider the fact that this has the potential to be immensely destructive of cervid herds. As a result, to trust solely in genetic resistance seems like too large a gamble.”

“Well, we worked on developing the vaccine using an attenuated rabies virus. This vaccine is completely administrable via oral pathway. Now this is in contrast to another study out of New York that claimed to have made some breakthroughs using an attenuated Salmonella vaccine. Besides many other problems with that study, the vaccine had to be applied repeatedly directly to the tonsils. Our vaccine would be a one-time dose, with no follow-ups required. To distribute it, we would simply go to people like yourself, with your outfitting business, and have it distributed in your bait-sites. As the deer congregate to eat the grain, they are also getting their dose of CWD vaccine.”

“Do you think that vaccinating the wild could potentially create a sort of ‘vaccine dependence,’ where we keep all these susceptible animals alive and contributing their genes to the population when they should have died? Are we setting ourselves up to have to keep applying the vaccine indefinitely, or else face a massive outbreak due to so many susceptible genes in the herd?”

Could widespread use of a vaccine lead to vaccine-dependence by ensuring the propagation of CWD-susceptible genes in the gene pool?

Could widespread use of a vaccine lead to vaccine-dependence by ensuring the propagation of CWD-susceptible genes in the gene pool? “That’s very true,” I agreed. “On a farm, routine vaccination is no problem. In the wild though, to commit to 100 years of vaccinations is pretty intense. But then again, if it is that or potentially watch cervids face extinction, that’s clearly something that should be done.”

“That’s right,” he nodded. “But it may be more of a cyclical 10-year strategy where the vaccine needs to be redistributed every 10 years. It would be a big undertaking, but maybe not as bad as it seems looking at it from this side.”

He nods, and states “Personally, I think it’s [ridiculous]. Quite often what you get with any infection is a secondary infection. Likely, this is correlation, not causation. Prion diseases ravage your immune system, so becoming infected with a prion disease could make you more susceptible and hospitable to a certain type of bacteria. It’s similar to Johne’s disease in cattle. The agent that causes Johne’s disease, when we look into people with Krohn’s disease, we find the same bacteria there. But what it may be is that when you have chronic inflammation of the gut (a common symptom between both diseases) the bacteria are able to colonize the host and make a home there. The bacteria are a result of the disease, not vice-versa. So while those questions need to be asked and avenues explored, no, we are past that point in the science now. I can’t even remember the last time I was at a prion conference and someone presented that with a straight face.”

*Note: Dr. Bastion is the scientist who is currently being touted in hunting communities as 'having found a cure' for CWD. Watch for a blog update on that, however, these claims are extremely exaggerated and misleading at best. He has not found a cure and, as Dr. Napper points out, is likely pursuing a deeply-flawed line of research that will lead to nothing.*

“Oh absolutely,” he agreed. “That’s why we are being careful to account for that. That's why targeting all 3 DSE’s would be ideal. Think of it like if I took a swing at you. You might be able to avoid one swing, but if I try two punches and a kick, chances are at least one is going to connect.” I wondered if this example indicated that he was getting tired of having me in his office but his laugh indicated otherwise. “So that’s why we were pushing for a multi-valent vaccine—a vaccine developed in Saskatchewan would work equally well for reindeer in Norway.”

“And what is the current state of this research now?” I asked. “Is it still being tested?” Scott shook his head, a wry smile crossing his face. “No. Sadly, after getting so close and having two more vaccines already developed and awaiting testing, they have cut us off, and it is sitting on a shelf now, waiting for new funding.”

I shook my head in disbelief. “But this sounds so huge! And the cure might be literally already in hand, sitting on a shelf! Why would they do that?”

“Well, getting funding has a lot to do with politics. Funding goes where the politicians think it will get them the most votes. And reality is that a lot of people have no idea what CWD is, [and BSE is not as large an issue as it once was, and Creutzfeldt-Jacobs disease, while severe, only infects a very small percentage of the population].If you ask someone in Toronto when the last time they saw a deer was, the reply might be ‘never.’ And so for the areas with the most votes, the loss of deer would be unfortunate, but hardly an impact on their lives [or so they think]. So funding opportunities shift to different diseases. And unfortunately, running a lab is also like running a business, and we need to be kind of opportunistic. I have employees whose paycheques depend on my ability to secure funding. So sadly, when the funding for CWD just isn’t there, as disappointing as it is with two potential vaccines sitting on a shelf, I have to focus on where the funding is. And to me it’s so short-sighted. I mean, this has the potential to be an absolute disaster—it already is in the cervid industry—and it could become so much worse. And they spent ten years funding it to the point where we were right on the edge of this breaking point, and then they went ‘you know what? That just doesn’t seem to be what we want to send funding towards anymore.’ It’s the nature of the game I guess, but it’s so frustrating.”

“It would be that the vaccine is essentially an extra layer of defense. If we created this vaccine, fair warning: there is a chance that it still might not be the perfect answer [especially in the wild]. But it’s equally plausible that genetic resistance is not the complete answer either. What it might be is that genetic resistance, coupled with a vaccine, together can force Dr. Haley’s ‘ladder’ high enough that deer no longer get CWD, regardless of the level of environmental contamination with prions. Adding live diagnostic tools to the tool kit as well, then between these three, we should really be able to get it under control in the cervid industry at least.”

And that was a good place to end it, I thought. Once again, I was seeing how important it is that we work together as an industry, recognizing the value in other research, even if it is not the ‘answer’ that we ourselves subscribe to. Just as deer farmers and hunters need to work together as a cohesive group to maintain a positive public image and to prevent the spread of CWD, we also need to work together in exploring the options that exist to combat, and potentially cure, the disease. So let’s not denounce valid research simply because we think there is a better option, or (heaven forbid) we want to downplay the severity of the disease. Let’s celebrate the successes of each research branch as they come, and support them as they encounter obstacles. Just as we need to celebrate and support each other in the hunting community. Remember, we’re all in this together.

If you haven't read the prequel to this blog, where I interview Dr. Nicholas Haley about genetic resistance to CWD, make sure to check it out!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed